The COVID-19 pandemic presented unprecedented challenges for global value chains (GVCs) and aggravated an already difficult situation stemming from geopolitical tensions and policy uncertainties. While gross exports declined by around 10 percent in 2020 compared to the previous year, GVC exports fell by a higher 12 percent indicating a decline in GVC participation. The pandemic resulted in significant readjustments in demand and supply responses. Supply shocks emanated from the closure of factories due to containment and social distancing measures, first in China and then the rest of the world as the pandemic spread, disrupting downstream industries. The demand shock was more varied as quarantine measures and lockdown had a differential impact across sectors. For example, remote working and health pressures led to a surge in demand for information and communication goods, electronic products, pharmaceuticals, medical equipment and online services. In contrast, demand plummeted for industries that require face to face interactions like airlines, tourism, and hotels and restaurants.

In this article, we ascertain the impact of COVID-19 shock on GVCs through a variety of lenses. This is an important issue for economies in Asia where GVCs played an important role in transforming economies by providing opportunities from technology upgrading and efficiency improvements. We find that COVID-19 adversely impacted GVC participation with the impact being more prominent for emerging and developing economies compared to advanced economies. At the sectoral level, the manufacturing sector was more impacted compared to the primary and services sectors. Countries which are more downstream and whose exports depend on inputs from other countries were also hit harder than countries that produce these intermediate inputs. At the same time, GVCs have exhibited a strong degree of resilience as argued in the Asian Infrastructure Finance (AIF) report on Sustaining Global Value Chains (2021). We find that there has not been any widespread reshoring of production from emerging and developing economies to advanced economies. Recent trade data suggests that GVC firms across many countries were successful in substituting foreign inputs with locally sourced materials.

How Did the COVID-19 Pandemic Impact GVC Participation?

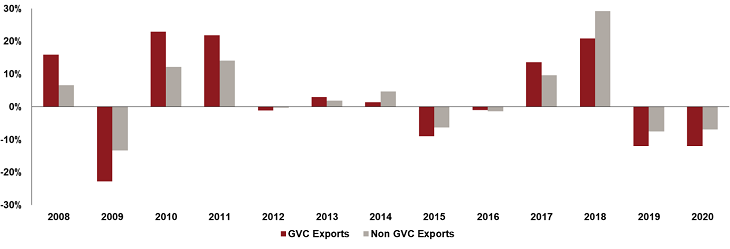

GVCs have proven to be more resilient to the pandemic compared to previous shocks over the past 15 years. As shown in Figure 1, the contraction in GVC exports in 2020 was roughly half of what was witnessed during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009. Moreover, past trends also suggest that GVC exports are likely to bounce back strongly as what happened in the post-GFC period.

Figure 1: Growth in Total and Global Value Chain Export

GVC = Global Value Chains

Source: Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input Output modeling (MRIO) database and authors’ calculations.

A key challenge in identifying how the COVID-19 pandemic affected GVC participation is to isolate this impact from other developments that took place in the pre-COVID period. These include a decline in GVC participation rate in recent years—as highlighted in the AIF and the World Bank World Development Report on Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains (2020)— and a rise in protectionist measures across several countries, including United States and China.

To sequester the COVID-19 impact, the weighted average growth of GVC participation between 2010 and 2017 was calculated. It was then assumed that in absence of the pre-COVID developments and COVID-19 pandemic, GVC participation would have continued to grow at the average rate during 2018 to 2020. The difference between the actual GVC participation and predicted GVC participation in 2018 and 2019 was assumed to be the impact of pre-COVID developments, including the rise in trade restrictions. In 2020, this impact was augmented by the pandemic so the difference between the actual and predicted GVC participation can be attributed to both the pre-COVID and COVID shocks. The impact of the pre-COVID shock was then deducted from the total shock in 2020 to isolate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic shock.

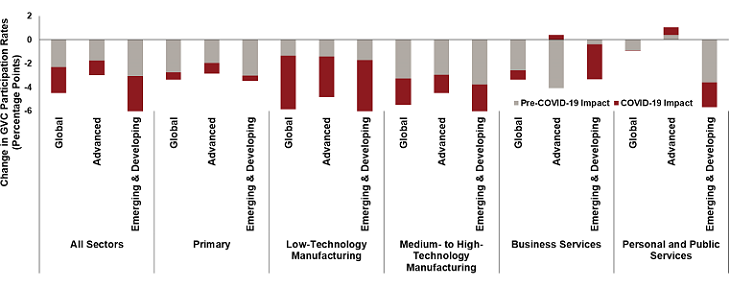

The contraction in GVC participation due to the COVID-19 pandemic was broad-based with most economies and sectors experiencing a decline compared to the baseline (Figure 2). However, the emerging and developing economies were hit harder, experiencing a three-fold higher decline in GVC participation compared to advanced economies. This has reversed some of the GVC participation gains made over the last two decades by emerging and developing economies, including several in Asia like Bangladesh, Viet Nam, Thailand, Indonesia and India.

Figure 2: Impact of Recent Shocks on GVC Participation

GVC = Global Value Chains

Source: Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input Output modeling (MRIO) database and authors’ calculations.

Both low-technology and medium- to high-technology manufacturing GVC exports were hit hard by the pandemic, although the low-technology sectors were hit harder. This is not surprising as the low-technology manufacturing sectors tend to be more labor-intensive and were more impacted by social distancing measures. Some of the hardest hit sectors were leather products and footwear, textiles and textile products and food, beverages and tobacco, with GVC participation rates declining by 8.5, 5.8 and 3.9 percentage points respectively due to COVID-19 shock. Construction, another labor-intensive sector, also experienced a decline of 3.8 percentage points in GVC participation. Several medium- to high-technology manufacturing sectors were also impacted, likely due to supply disruptions of inputs with transport equipment, chemical products, machinery and electrical and optical instruments and experiencing a decline of 2.7, 2.6, 2.1 and 1.4 percentage points respectively in their GVC participation as a result of the pandemic. Emerging and developing economies also witnessed a sharper drop in the GVC participation of services, with hotels and restaurants, various transport services and retail trade being the most impacted. In contrast, advanced economies witnessed an uptick driven by health, education, financial intermediation and post and telecommunication services.

Supply and Demand Shocks

As pointed out above, GVCs were impacted by the pandemic through both supply and demand shocks. Countries were impacted in a heterogenous manner depending on their vulnerability to foreign supply and demand shocks in GVCs. In GVCs, individual countries only contribute a part of the value added in exports while sourcing the rest from other countries. Thus, countries where foreign value added constitute a higher share of exports are more exposed to foreign supply shocks, including lockdowns in source countries, disrupting the supply of raw materials. Conversely, a higher reliance on domestic value added can increase a country’s vulnerability to demand shocks. This is especially true for smaller economies that provide inputs to downstream industries.

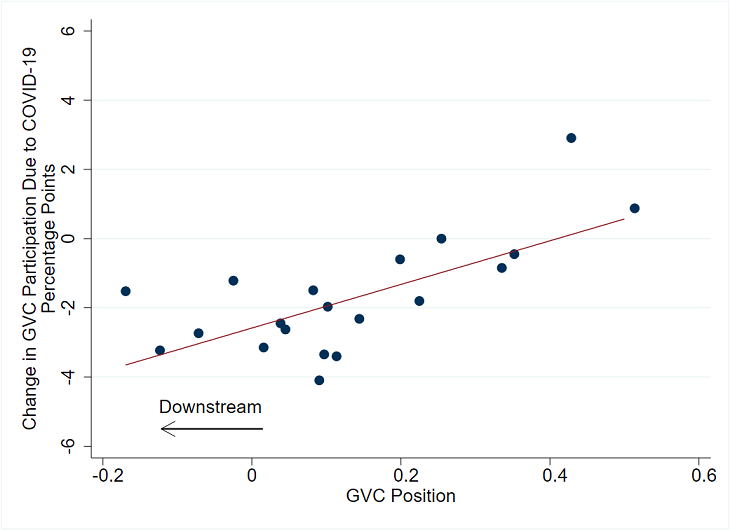

Figure 3: Global Value Chains Position and Impact of COVID-19

GVC = Global Value Chains

Source: Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input Output modeling (MRIO) database and authors’ calculations.

Figure 3 highlights the relationship between GVC position and the impact of COVID-19. The former characterizes the average position of a country in a value chain by comparing the extent to which its exports are made up of domestic intermediate inputs with foreign intermediate inputs. A positive value would mean that the country supplies more domestically produced intermediate inputs than its use of foreign intermediate inputs. As can be seen from Figure 3, countries which are downstream, i.e., rely more on foreign intermediate inputs in their exports, witnessed a greater decline in GVC participation due to COVID-19. This is not surprising as downstream industries are likely to be most affected by supply side disruption emanating in any part of the value chain.

Did COVID-19 Accelerate Reshoring?

There has been speculation that the supply chain risks due to the COVID-19 pandemic could intensify reshoring of production from emerging economies to advanced economies. Even prior to the pandemic, the possibility of reshoring has been under discussion given advancements like Industry 4.0’s labor-saving technologies that have reduced the cost of production in advanced economies, as well as protectionist trade policies.

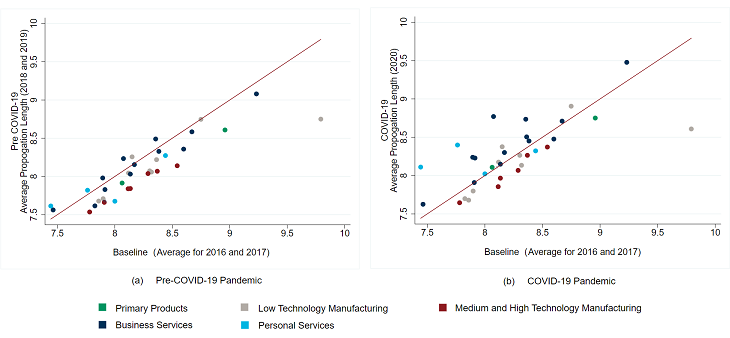

A reshoring of production stages from emerging economies to advanced economies is expected to shorten the length of the GVCs. According to the methodology outlined in Wang et al. (2017) and Antràs and Chor (2018), the length of the GVCs, or the average number of stages separating primary inputs and final consumption in GVCs, had increased from 7.9 in 2000 to 8.5 in 2010 and further to 8.7 in 2013. However, there has been a decline since 2015, consistent with global slowbalization. Figure 4a indicates a broad-based decline in GVC length across the sectors in 2018 and 2019 when the trade tensions intensified compared to 2016 and 2017. Barring rubber and plastics, all other manufacturing sectors experienced a shortening of GVC length. A survey of nearly 2,500 manufacturing firms across eight European countries in 2015 identified flexibility in logistics and product quality as the key drivers for reshoring their production.

Figure 4: Change in Global Value Chain Length by Sectors

Source: Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input Output modeling (MRIO) database and authors’ calculations.

Several studies including Seric and Winkler (2020) pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic could accelerate reshoring as it reduces the risks from disruptions in other countries impacting the supply chain and allows for more flexible adjustment to changing demand. Both would mitigate the risks of firms in the event of a pandemic or other shock. However, initial evidence from 2020 GVCs show little evidence of reshoring or shortening of GVC length. GVC length across most sectors either increased or remained stagnant in 2020 compared to 2018 and 2019 (Figure 4b). This could be a result of lead firms successfully scouting for alternate sources for intermediate inputs even as containment measures impacted supply response from the original sources. For example, the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in China in the first quarter of 2020 resulted in Chinese exports to the United States contracting by 37.1 percent. In contrast, exports from other ASEAN economies surged with exports from Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia and Viet Nam growing by 41.2 percent, 15.1 percent, 13.9 percent and 12.5 percent respectively, reflecting some substitution effect. With exports from China recovering in the second half of 2020, and COVID-19 spreading to other parts of Southeast Asia, the trend reversed sharply.

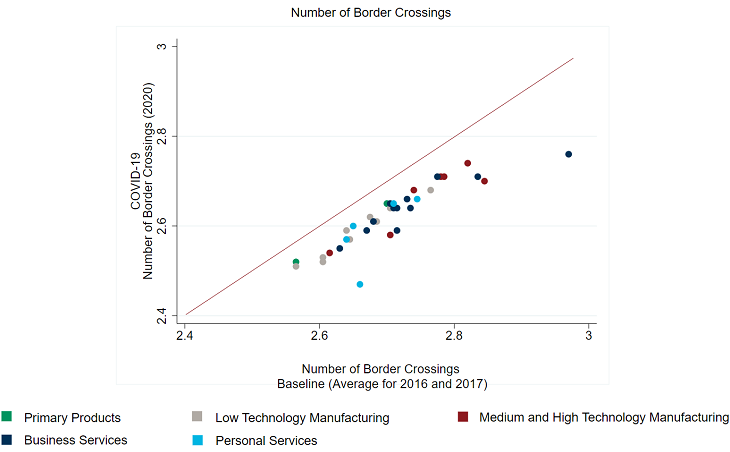

Figure 5: Border Crossings During COVID-19

Source: Asian Development Bank Multi-Regional Input Output modeling (MRIO) database and authors’ calculations.

To get a better sense of the change in GVC length, the GVC length was decomposed to (a) domestic segment (b) foreign segment and (c) number of border crossings. It was found that there has been an increase in the foreign segment of GVC, i.e., the number of stages of production in the partner country as well as some increase in the domestic segment, which involves the number of stages in the home country. However, as shown in Figure 5, there has been a broad-based reduction in the number of border crossings in 2020 compared to the average for 2018 and 2019. Thus, it is likely that GVC firms at home and abroad overcame the bottlenecks arising out of reduced border crossings by lengthening the supply chain domestically. For example, if due to lockdowns, cross border intermediate inputs were not available, then firms at home and abroad were successful in procuring substitutes within their own territories.

References

AIIB. 2021. Asian Infrastructure Finance 2021: Sustaining Global Value Chains. Beijing.

Antràs, P., and Chor, D. 2018. “On the Measurement of Upstreamness and Downstreamness in Global Value Chains”. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 24185. DOI 10.3386/w24185

UNIDO. 2019. Industrial Development Report 2020: Industrializing in the Digital Age.

Seric, A., and Winkler, D. 2020. “COVID-19 Could Spur Automation and Reverse Globalization —To Some Extent”. VOX EU. April 28.

Wang, Z., Wei, S., Yu, X., and Zhu, K. 2017. “Characterizing Global Value Chains: Production Length and Upstreamness”. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 23261. DOI 10.3386/w23261.

World Bank. 2020. World Development Report 2020 Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chains.

1 Authors’ Notes: The authors are very thankful to Jang Ping Thia, Manager, Economics Department, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) for the valuable comments.

2 Senior Economist, Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Beijing, China. Email: abhijit.sengupta@aiib.org

3 Associate Professor, Research Institute for Global Value Chains, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China. Email: zhaojingthu@126.com